Lunar Thermoelectric Generator NASA MINDS

Project Overview

NASA MINDS is a national collegiate competition to develop something novel for the Artemis program. For this competition, we designed and tested a lunar thermoelectric generator system which uses waste heat and the natural temperature gradient of the lunar regolith to generate electricity on the moon. We received NASA funding to construct and test the proposed thermoelectric system, and validated our results with thermal simulations. We received first place for our technical paper, and fourth place overall.

After the competition, we conducted more comprehensive experiments which investigated design characteristics to improve the efficiency the heat conductor assembly. We presented an research paper at IEEE MIT URTC 2021, which was published in IEEE Xplore and is public on arXiv.

Concept

There is a large temperature difference between the soil on the moon’s surface and just a few feet underground. This is because lunar soil’s thermal conductivity increases with depth as it becomes more compact and dense. This project theorized that lunar soil underground with higher thermal conductivity at could be used as a heat sink for a thermoelectric generator powered by solar radiation or waste heat from a lunar base.

This can be done by extending the cold side of the thermoelectric plates with a copper “radiator cylinder” to reach depths with a high thermal conductivity. The top of the radiator cylinders provides a heat sink at the surface that can be utilized in conjunction with any heat source to generate electricity.

This concept was successfully demonstrated experimentally, and the results are detailed in the paper above. The rest of this article will focus on the design and simulation of the device and test apparatus.

Design

To test this concept experimentally, we built a prototype device and test apparatus to simulate the thermal conditions of the moon. This was done by conducting the experiment in a vacuum, providing heat to the surface via radiation, and creating a heat sink in the soil similar to what exists on the moon.

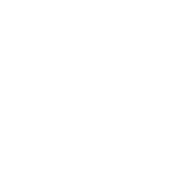

The prototype device consisted of thermoelectric generator modules at the surface, sitting on a modular radiator cylinder assembly. The radiator cylinders were concentric copper cylinders which could be reconfigured for different experiments. The radiator cylinders were insulated from surface heat bleed with aerogel and enclosed in a steel pipe to simulate how they may acutally be deployed.

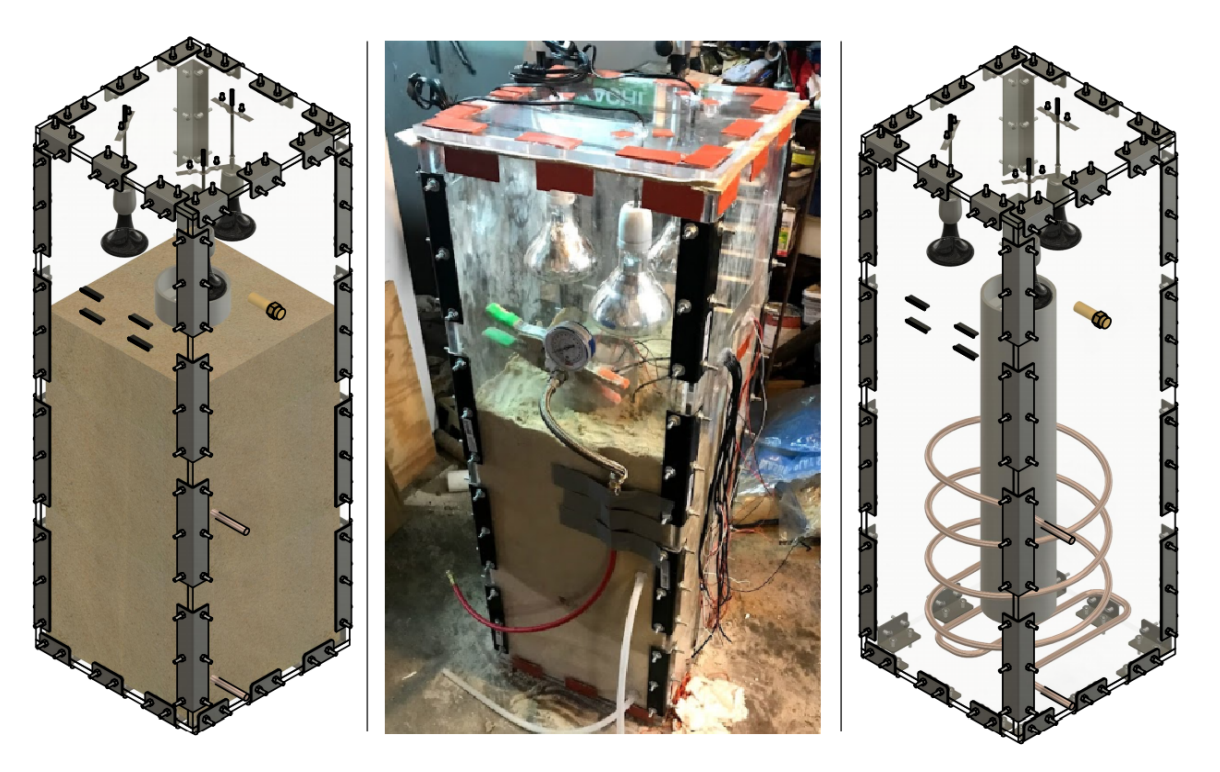

For the vacuum chamber, we made a 16” x 16” x 48” acrylic box with 1/2” thick sheets, with holes for wires, pipes, and bolts. The radiative heat source was three heat lamps that hung above the surface. Our lunar soil simulant was sand, which has the desired property of increasing its thermal conductivity with depth. The “heat sink” was created by water in copper coils cooled to room temperature by a PID water cooling system. This kept the soil below a certain depth at a constant temperature, and created a temperature gradient in the first 20 cm of sand similar top what exists on the moon.

Temperature at 9 locations was recorded by thermocouples embedded in the sand and prototype device. Temperature data, as well as voltage produced by the thermoelectric generator, were collected by Arduino Uno, and written to a csv by a Raspberry Pi.

Simulation

We used FEA thermal simulation in Fusion 360 to validate our experimental results. As described in the paper, the surface and subsurface temperatures in the simulation were significantly higher than in the experiment, but the temperature differential we were trying to create between the plates of the thermoelectric generator was accurately modeled. We also used simulations to design a heat sink in a way that would replicate the temperature distribution of lunar soil, and determine the required wall thickness of the vacuum chamber.

This was my first exposure to simulations. While Fusion 360 is definitely not a real simulation software, it’s all we had access to, and it made learning Ansys for Purdue Space Program feel like a natural transition.